(aktualisiert 21.09.2013)

JPMorgan's London Whale Skandal

Vorwort

Der Fall "London Whale" entlarvt auf einen Schlag, dass das amerikanisch-britische Finanzsystem so weiter macht, wie vor der Finanzkrise. Alle Spieler - die üblichen Verdächtigen - werden auf frischer Tat ertappt: Wall Street und City, Too-Big-To-Fail-Banken, Hedge-Fonds und Schattenbanken, hemmungslose und auf den Zusammenbruch von Euro und ganzen Staaten spekulierende Trader und Milliardäre, überbezahlte Banker, antiregulatorische Bankenlobby, Stresssicherheit verbreitende Federal Reserve und untätige Aufsichts- und Justizbehörden. Die Banken haben sich durch steuerlich abzugsfähige Milliardensummen von ihrer Verantwortung freigekauft und die für sie handelnden Personen wurden nie von den Gerichten persönlich belangt, Geschweige denn ins Gefängnis gebracht. Die Zinsen wurden praktisch abgeschafft und die Märte mit Geld überschwemmt. Die USA verweigern sich immer noch einer Sparpolitik und denken nur an ihre Kriege und Präsidentenwahlen. Die wenigen sparwilligen Politiker in Europa, wie z.B. in Griechenland, Großbritannien und Deutschland, werden angefeindet und unter Druck gesetzt. Dringend notwendige Reformen wie der Fiskalpakt oder der Dodd-Frank-Act werden in die Länge gezogen und verwässert. Was ein Glück, dass Autoren, Blogger und Journalisten dem Ganzen keinen Glauben schenkten, sondern weiter die Finanzkrise untersucht und Missstände aufgezeigt haben!

Zur Hilfe kommt am 15. März 2013 unerwarteterweise der von den Demokraten dominierte US-Senat mit seinem Ausschuss PIS mit einem Bericht und einem Hearing. Es wird auf einmal klar, dass Jamie Dimon selbst involviert war. Die Zeit scheint gekommen, wo die Too-Big-To-Fail-Banken aufgespalten, die Volcker-Rule durchgesetzt und die Too-Big-Too-Jail-Banker strafrechtlich zur Verantwortung gezogen werden.

Schließlich verhängen am 19.09.2013 die Aufsichtsbehörden Fed, SEC, OCC und FCA Geldbußen in Höhe von $920 Mio. Das entspricht dem Gewinn von 13

Geschäftstagen!

Übersicht

- Bußgelder vom 19.09.2013

- Senate Banking Hearing 15.03.2013

- London Whale

- Wette

- Wellen

- Aufdeckung

- Vertuschung

- Bekanntgabe

- Aufklärung

- Hochmut und Fall

- Schmutzige Hände

- Nicht-Überraschungen

- Gewinner

- Fehler

- Wirtschaftliche Konsequenzen

- Personelle Konsequenzen

- Firmeninterne Konsequenzen

- Regulatorische Konsequenzen

- Juristische Konsequenzen

- Offene Fragen

- Anhörung im Senate Banking Committee

- Dokumente

Bußgelder von Fed, SEC, OCC, FCA - 19.09.2013

Am 19.09.2013 präsentieren die Aufsichtsbehörden JPMorgan die Rechnung: Civil Penalties Fed $200 Mio, SEC $200 Mio, OCC $300 Mio und FCA (UK) $220 Mio. Jamie Dimon und die Manager bleiben unbehelligt (Too Big to Jail).

Press Release der Fed vom 19.09.2013:

The Federal Reserve Board on Thursday announced that JPMorgan Chase & Co., New York, New York (JPMC), a registered bank holding company, will pay a $200 million penalty for deficiencies in the bank holding company's oversight, management, and controls governing its Chief Investment Office (CIO).

The consent Order of Assessment of a Civil Money Penalty against JPMC cites the failure by JPMC to appropriately inform its board of directors and the Federal Reserve of deficiencies in risk-management systems identified by management. On January 14, 2013, the Board issued a consent Cease and Desist Order requiring JPMC to take prompt action to correct these deficiencies, which represented unsafe or unsound practices at JPMC. The Board's Cease and Desist Order followed the disclosure of significant losses in a large synthetic credit portfolio that was managed by the CIO.

The Board's action on Thursday was taken in coordination with the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Securities and Exchange Commission, and the Financial Conduct Authority of the United Kingdom. The penalties issued by the agencies total approximately $920 million.

Press Release der SEC vom 19.09.2013:

The Securities and Exchange Commission today charged JPMorgan Chase & Co. with misstating financial results and lacking effective internal controls to detect and prevent its traders from fraudulently overvaluing investments to conceal hundreds of millions of dollars in trading losses.

The SEC previously charged two former JPMorgan traders with committing fraud to hide the massive losses in one of the trading portfolios in the firm’s chief investment office (CIO). The SEC’s subsequent action against JPMorgan faults its internal controls for failing to ensure that the traders were properly valuing the portfolio, and its senior management for failing to inform the firm’s audit committee about the severe breakdowns in CIO’s internal controls.

JPMorgan has agreed to settle the SEC’s charges by paying a $200 million penalty, admitting the facts underlying the SEC’s charges, and publicly acknowledging that it violated the federal securities laws.

“JPMorgan failed to keep watch over its traders as they overvalued a very complex portfolio to hide massive losses,” said George S. Canellos, Co-Director of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement. “While grappling with how to fix its internal control breakdowns, JPMorgan’s senior management broke a cardinal rule of corporate governance and deprived its board of critical information it needed to fully assess the company’s problems and determine whether accurate and reliable information was being disclosed to investors and regulators.”

As part of a coordinated global settlement, three other agencies also announced settlements with JPMorgan today: the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority, the Federal Reserve, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. JPMorgan will pay a total of approximately $920 million in penalties in these actions by the SEC and the other agencies.

According to the SEC’s order instituting a settled administrative proceeding against JPMorgan, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 established important requirements for public companies and their management regarding corporate governance and disclosure. Public companies such as JPMorgan are required to create and maintain internal controls that provide investors with reasonable assurances that their financial statements are reliable, and ensure that senior management shares important information with key internal decision makers such as the board of directors. JPMorgan failed to adhere to these requirements, and consequently misstated its financial results in public filings for the first quarter of 2012.

According to the SEC’s order, in late April 2012 after the portfolio began to significantly decline in value, JPMorgan commissioned several internal reviews to assess, among other matters, the effectiveness of the CIO’s internal controls. From these reviews, senior management learned that the valuation control group within the CIO – whose function was to detect and prevent trader mismarking – was woefully ineffective and insufficiently independent from the traders it was supposed to police. As JPMorgan senior management learned additional troubling facts about the state of affairs in the CIO, they failed to timely escalate and share that information with the firm’s audit committee.

Among the facts that JPMorgan has admitted in settling the SEC’s enforcement action:

- The trading losses occurred against a backdrop of woefully deficient accounting controls in the CIO, including spreadsheet miscalculations that caused large valuation errors and the use of subjective valuation techniques that made it easier for the traders to mismark the CIO portfolio.

- JPMorgan senior management personally rewrote the CIO’s valuation control policies before the firm filed with the SEC its first quarter report for 2012 in order to address the many deficiencies in existing policies.

- By late April 2012, JPMorgan senior management knew that the firm’s Investment Banking unit used far more conservative prices when valuing the same kind of derivatives held in the CIO portfolio, and that applying the Investment Bank valuations would have led to approximately $750 million in additional losses for the CIO in the first quarter of 2012.

- External counterparties who traded with CIO had valued certain positions in the CIO book at $500 million less than the CIO traders did, precipitating large collateral calls against JPMorgan.

- As a result of the findings of certain internal reviews of the CIO, some executives expressed reservations about signing sub-certifications supporting the CEO and CFO certifications required under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

- Senior management failed to adequately update the audit committee on these and other important facts concerning the CIO before the firm filed its first quarter report for 2012.

- Deprived of access to these facts, the audit committee was hindered in its ability to discharge its obligations to oversee management on behalf of shareholders and to ensure the accuracy of the firm’s financial statements.

The SEC’s order requires JPMorgan to cease and desist from causing any violations and any future violations of Sections 13(a), 13(b)(2)(A), and 13(b)(2)(B) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rules 13a-11, 13a-13, and 13a-15. The order also requires JPMorgan to pay a $200 million penalty that may be distributed to harmed investors in a Fair Fund distribution.

The SEC’s investigation, which is continuing, has been conducted by Michael Osnato, Steven Rawlings, Peter Altenbach, Joshua Brodsky, Joseph Boryshansky, Daniel Michael, Kapil Agrawal, Eli Bass, Sharon Bryant, Daniel Nigro, and Christopher Mele. The SEC appreciates the coordination of the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority, Federal Reserve, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency as well as the assistance of the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and Public Company Accounting Oversight Board.

Press Release des OCC vom 19.09.2013:

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) announced today a $300,000,000 civil money penalty (CMP) action against JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., for unsafe and unsound practices related to derivatives trading activities conducted on behalf of the bank by the Chief Investment Office (CIO).

The OCC found that the bank’s controls failed to identify and prevent certain credit derivatives trading conducted by the CIO that resulted in substantial loss to the bank, which has exceeded $6 billion. The OCC has conducted several targeted exams which found the following deficiencies related to the credit derivatives trading practices conducted by the CIO: inadequate oversight and governance to protect the bank from material risk, inadequate risk management processes and procedures, inadequate control over pricing of trades, inadequate development and implementation of models used by the bank, and inadequate internal audit processes.

Concurrent with the OCC's enforcement action, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System assessed a $200,000,000 penalty, the Securities and Exchange Commission assessed a $200,000,000 penalty and the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) assessed a penalty of 137,610,000 pounds, or approximately $220,000,000. The Federal Reserve and SEC actions are against the bank’s holding company, while the OCC and FCA actions are against the bank.

The CMP follows a cease and desist order issued in January 2013 that directed the bank to correct deficiencies in its derivatives trading activity.

Press Release der FCA Financial Conduct Authority UK:

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has fined JPMorgan Chase Bank N.A. (“JPMorgan”) £137,610,000 ($220 million) for serious failings related to its Chief Investment Office (CIO). JPMorgan’s conduct demonstrated flaws permeating all levels of the firm: from portfolio level right up to senior management, resulting in breaches of Principles 2, 3, 5 and 11 of the FCA’s Principles for Businesses - the fundamental obligations firms have under the regulatory system.

The breaches occurred in connection with the $6.2 billion trading losses sustained by CIO in 2012. These losses arose as a result of what became known as the “London Whale” trades, and were caused by a high risk trading strategy, weak management of that trading and an inadequate response to important information which should have notified the firm of the huge risks present in the CIO’s Synthetic Credit Portfolio (SCP).

Tracey McDermott, the FCA’s director of enforcement and financial crime said:

"When the scale of the problems at JPMorgan became apparent, it sent a shock-wave through the markets. Maintaining the integrity of markets is a key part of our wholesale conduct agenda. We consider JPMorgan’s failings to be extremely serious such as to undermine the trust and confidence in UK financial markets.

"This is yet another example of a firm failing to get a proper grip on the risks its business poses to the market. There were basic failings in the operation of fundamental controls over a high risk part of the business. Senior management failed to respond properly to warning signals that there were problems in the CIO. As things began to go wrong, the firm didn’t wake up quickly enough to the size and the scale of the problems. What is worse, they compounded this by failing to be open and co-operative with us as their regulator.

"Firms must learn the lessons from this incident and ensure that they have business practices, values and culture to control the risks in their businesses."

Summary of Kea Facts

The trading strategy for the SCP in 2012 caused the size of its positions to grow so large that it was at risk of substantial losses from even a small adverse market move.

However the firm’s response to breaches of relevant risk limits was to assume the numbers indicating a breach were unreliable or to doubt the accuracy of the methodology for risk measurement, and to approve temporary limit increases without adequate analysis of the root cause of the breaches.

When significant losses began to mount during 2012, JPMorgan’s traders sought to conceal them by mismarking positions and through misconduct in the market in which the losses were occurring. Mismarking went undetected in 2012 owing to flaws in valuation controls, some of which had existed since 2007.

JPMorgan’s failings extend to its senior management’s response to the problems with the SCP in the second quarter of 2012. In preparation for a regulatory filing (of J.P. Morgan Chase & Co (the Group)’s first quarter net income) on 10 May 2012, the firm’s senior management had commissioned a review of the SCP’s valuations. However the review failed to uncover the extent of the valuation problems present in the SCP. The firm’s senior management gave insufficient weight to inconsistencies raised in the information in its possession, especially in light of the context provided by the scale of the losses in the SCP. Firm senior management did not take sufficient steps to ensure that all crucial information reached the appropriate decision makers; findings made by Internal Audit were not escalated to senior management and therefore not considered as part of the review. In addition, the firm’s senior management did not involve key parts of the firm’s overall control framework in the review.

The Group filed a statement of its earnings in the US on 10 May 2012 which over-valued the SCP’s positions. It subsequently filed a restatement on 13 July 2012. More effective analysis of the information available as at 10 May 2012 may have prevented the need for this restatement.

JPMorgan also failed to meet its obligations in respect of its relationship with the FCA*. During the first half of 2012, JPMorgan failed to be open and co-operative with the FCA in that it concealed the extent of the losses as well as numerous serious and significant issues regarding the situation in the SCP.

JPMorgan’s failings were extremely serious and undermined trust and confidence in UK financial markets.

Settlement Discounts

JPMorgan agreed to settle at an early stage of the FCA’s investigation. JPMorgan therefore qualified for a 30% discount under the FCA’s settlement discount scheme. Without the discount the fine would have been £196,586,000.

Overseas Regulators

This was a significant cross-border investigation, and the FCA would like to thank the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, New York Federal Reserve Bank and the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission for their co-operation.

JPMorgan also agreed to settle actions brought by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, who imposed a financial penalty of $200 million and required the Firm to admit wrongdoing; the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, who imposed a financial penalty of $300 million, and the Federal Reserve, who imposed a financial penalty of $200 million.

* On 1 April 2013, the Financial Services Authority (FSA) became the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). References in this press release to the FCA should be read as to include reference to the FSA prior to 1 April 2013.

Notes for Editors:

- Principle 2 requires regulated firms to conduct their business with due skill care and diligence.

- Principle 3 requires regulated firms to take reasonable care to organise and control their affairs responsibly and effectively with adequate risk management systems.

- Principle 5 requires firms to observe proper standards of market conduct.

- Principle 11 requires firms to deal with their regulators in an open and cooperative way and to disclose to the FCA or PRA appropriately anything relating to their business of which the FCA or PRA would reasonably expect notice.

- On the 1 April 2013 the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) became responsible for the conduct supervision of all regulated financial firms and the prudential supervision of those not supervised by the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA).

- The FCA has an overarching strategic objective of ensuring the relevant markets function well. To support this it has three operational objectives: to secure an appropriate degree of protection for consumers; to protect and enhance the integrity of the UK financial system; and to promote effective competition in the interests of consumers.

JP Morgan Execs Hearing im US-Senat

Risikomanagment

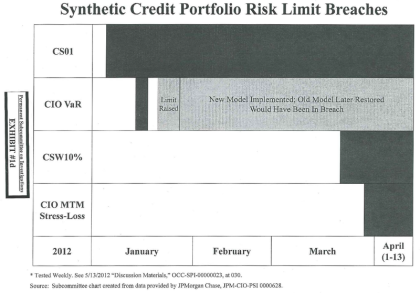

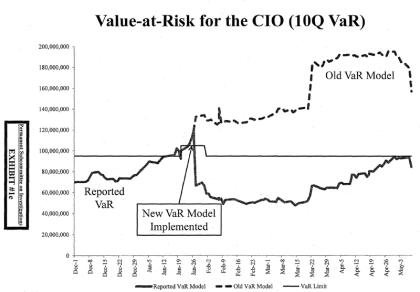

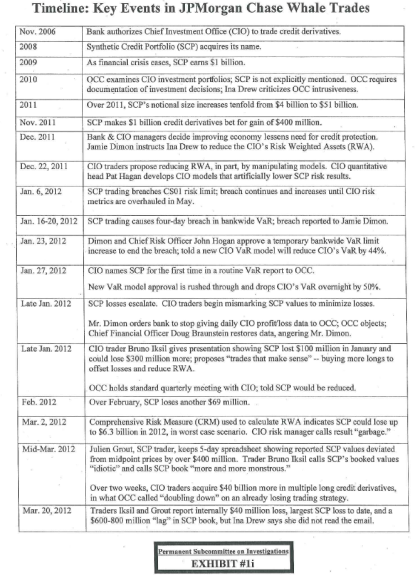

Der Senate Report deckt auf, dass JPMorgan bereits am 16. Januar 2012 vier Tage lang das maximale Risiko (VaR) sowohl für das Chief Investment Office CIO als auch für die gesamte Bank überschritten hat. Das Senior Management inkl. Dimon wurden informiert und Dimon erlaubte daraufhin die Anhebung der Grenzen.

Bereits im Februar 2012 meldete die Risikokennziffer CRM Comprehensive Risk Measure ein jährliches Verlustrisiko $6,3 Mrd. Die Zahl wurde als "Garbage" von Head of Market Risk im CIO Weiland bezeichnet. Tatsächlich trat aber genau diese Verlusthöhe letztendlich ein.

JPMorgan verwendete folgende 5 Risikolimits für das Synthetic Credit Portfolio SCP:

- VaR Value-at-Risk (gebrochen im Januar 2012)

- CS01 Credit Spread Widening 01 (um 1 Basisipunkt) wurde ab Anfang Januar immer wieder gebrochen (Jan 100%, Anfang Feb 270%, Mitte April sogar um 1000% überschritten).

- CSW10% Credit Spread Widening 10% (im März mehrfach gebrochen)

- Stress Loss Limits CIO MTM (im März alarmiert)

- Stop Loss Advisories

Diese Risikolimits wurden in folgender Häufigkeit gebrochen:

Q4, 2011: 6x

Q1, 2012: 170x

Apr. 2012: 160x

Ende März 2012 wurden zwar keine weiteren Trades gemacht, jedoch wurden alle 5 Risikolimits gleichzeitig gebrochen.

Angesichts der steigenden Verluste aus dem London Whale wurde am 27. Januar 2012 eigens das Risikomodell VaR geändert, wodurch der Risikoausweis sich über Nacht um 50% reduzierte. Später wurde das neue VaR-Modell wieder durch das alte ersetzt.

Jamie Dimon's Verwicklung:

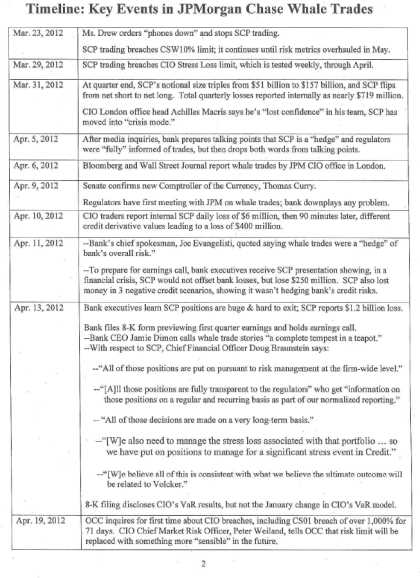

Entgegen aller bisherigen Behauptungen war Dimon über alle Entwicklungen im CIO von Anfang an informiert. Er genehmigte selbst am 23. Januar 2012 die Anhebung der Risikolimits, nachdem das SCP vier Tage lang das Risikolimit der gesamten Bank sprengte ("I approve").

Ermittlungsergebnisse des Senats

1.

JPMorgan’s Chief Investment Office rapidly amassed a huge portfolio of synthetic credit derivatives, in part using federally insured depositor funds, in a series of risky, short-term trades, disclosing the extent of the portfolio only after intense media exposure. In just a few months during 2011, as shown in Chart 1, the Chief Investment Office’s Synthetic Credit Portfolio grew from a net notional size of $4 billion to $51 billion, and then tripled in the first quarter of 2012 to $157 billion. That exponential growth in holdings and risk occurred with virtually no regulatory oversight.

2.

Once the whale trades were exposed, JPMorgan claimed to regulators, investors and the public, that the trades were designed to hedge credit risk. But internal bank documents failed to identify the assets being hedged, how they lowered risk, or why the supposed credit derivative hedges were treated differently from other hedges in the Chief Investment Office. If these trades were, as JPMorgan maintains, hedges gone astray, it remains a mystery how the bank determined the nature, size, or effectiveness of the so-called hedges, and how, if at all, they reduced risk.

3.

The Chief Investment Office internally concealed massive losses in the first several months of 2012 by overstating the value of its synthetic credit derivatives. It got away with overstating those values within the bank, even in the face of disputes with counterparties and two internal bank reviews.

As late as January 2012, the CIO had valued its credit derivatives by using the midpoint in the daily range of “bids” and “asks” offered in the marketplace. That’s the typical way to value derivatives. But beginning in late January, the traders stopped using midpoint prices and started using prices at the extreme edges of the daily price range to hide escalating losses. In recorded phone conversations, one trader described these marks as “idiotic.”

At one point, traders used a spreadsheet to track just how large their deception had grown by recording the valuation differences between using midpoint and more favorable prices. In just five days in March, according to the traders’ own spreadsheet, the hidden losses exceeded $400 million. The difference eventually exceeded $600 million. Counterparties to the derivative trades began disputing the CIO’s booked values involving hundreds of millions of dollars in March and April.

Despite the obvious value manipulation, on May 10 – the same day JPMorgan announced that the whale trades had lost $2 billion – the bank’s controller concluded a special review and signed off on the CIO’s derivative pricing practices as “consistent with industry practices.” JPMorgan leadership has continued to argue that the values assigned by its traders to the Synthetic Credit Portfolio were defensible under accounting rules.

Yet in July 2012, the bank reluctantly restated its first-quarter earnings. It did so only after an internal investigation listened to phone conversations, routinely recorded by the bank, in which its traders mocked their own valuation practices.

Their mismarked values weren’t wrong simply because the traders intended to understate losses; they were wrong because they changed their pricing practices after losses began piling up, stopped using the midpoint prices they had used up until January, and began using aggressive prices that consistently made the bank’s reports look better. Until JPMorgan and others stop their personnel from playing those kinds of games, derivative values will remain an imprecise, malleable, and untrustworthy set of figures that call into question the derivative profits and losses reported by our largest financial institutions.

4.

When the CIO’s Synthetic Credit Portfolio breached five key risk limits, rather than reduce the risky trading activities, JPMorgan either increased the limits, changed the risk models that calculated risk, or turned a blind eye to the breaches.

As early as January 2012, the rapid growth of the Synthetic Credit Portfolio breached one common measure of risk, called “Value-at-Risk” or VaR, causing a breach, not just at the CIO, but for the entire bank. That four-day breach was reported to top bank officials, including CEO Jamie Dimon, who personally approved a temporary limit increase, and voila, the breach was ended. CIO employees then hurriedly pushed through approval of a new VaR model that, overnight, dropped the CIO’s purported risk by 50 percent. Regulators were told about that remarkable reduction in the CIO’s purported risk, but raised no objection to the new model at the time.

The credit derivatives portfolio breached other risk limits as well. In one case, it exceeded established limits on one measure, known as Credit Spread 01, by 1,000 percent for months running. When regulators asked about the breach, JPMorgan risk managers responded that it wasn’t a “sensible” limit and allowed the breach to continue. When still another risk metric, called Comprehensive Risk Measure, projected that the Synthetic Credit Portfolio could lose $6.3 billion in a year, a senior CIO risk manager dismissed the result as “garbage.” It wasn’t garbage; that projection was 100 percent accurate, but the derivatives traders thought they knew better. Downplaying risk, ignoring one risk warning after another, and pushing to reengineer risk controls to artificially lower risk results, flatly contradict JPMorgan’s claim to prudent risk management.

5.

At the same time the portfolio was losing money and breaching risk limits, JPMorgan dodged OCC oversight. It omitted CIO data from its reports to the OCC; failed to disclose the growing size, risk, and losses of the Synthetic Credit Portfolio; and delayed or tinkered with OCC requests for information by giving the regulator inaccurate or unresponsive information. In fact, when the whale trades first became public, the bank offered such blanket reassurances that the OCC initially considered the matter closed. It was only when the losses exploded that the OCC took another look

6.

The failure of regulators to act sooner can’t be excused by the bank’s behavior. The OCC also fell down on the job. It failed to investigate multiple, sustained risk limit breaches; tolerated incomplete and missing reports from JPMorgan; failed to question the bank’s new “value at risk” model that dramatically lowered the CIO’s risk rating; and accepted JPMorgan’s protests that the media reports about the portfolio were overblown. It was not until May 2012, after a new Comptroller of the Currency took the reins at the agency, that OCC officials instituted their first intensive inquiry into the Synthetic Credit Portfolio.

Again, with the lessons of the 2008 financial crisis so painfully fresh, it is deeply worrisome that a major bank should seek to cloak its risky trading activities from regulators, and doubly worrisome that it was able to succeed so easily for so long.

7.

When the whale trades went public, JPMorgan misinformed regulators and the public about the Synthetic Credit Portfolio. JPMorgan’s first public response to the April news reports about the whale trades was when its spokesperson, using prepared talking points approved by senior executives, told reporters on April 10, that the whale trades were risk-reducing hedges known to regulators. A more detailed description came in a conference call held on April 13 with investment analysts. During that call, Chief Financial Officer Douglas Braunstein made a series of inaccurate statements about the whale trades as shown in Chart 2: He said the trades had been put on by bank risk managers and were fully transparent to regulators; he said the trades were made on a very long-term basis; he said the trades were essentially a hedge; and he said the bank believed the trades were consistent with the Volcker Rule which prohibits high risk proprietary trading by banks. Those public statements on April 13 were not true. As late as May 10, bank CEO Jamie Dimon repeatedly described the synthetic credit trades as hedges made to offset risk, despite information showing the portfolio was not functioning as a hedge. The bank also neglected to tell investors the bad news that the derivatives portfolio had broken through multiple risk limits, losses had piled up, and the head of the portfolio had put management of the portfolio into “crisis mode.”

It was recently reported that the eight biggest U.S. banks have hit a five-year low in the percentage of deposits used to make loans. Their collective average loan-to-deposit ratio has fallen to 84 percent in 2012, down from 87 percent a year earlier, and 101 percent in 2007. JPMorgan has the lowest loan-to-deposit ratio of the big banks, lending just 61 percent of its deposits out in loans. Apparently, it was too busy betting on derivatives to issue the loans needed to speed economic recovery.

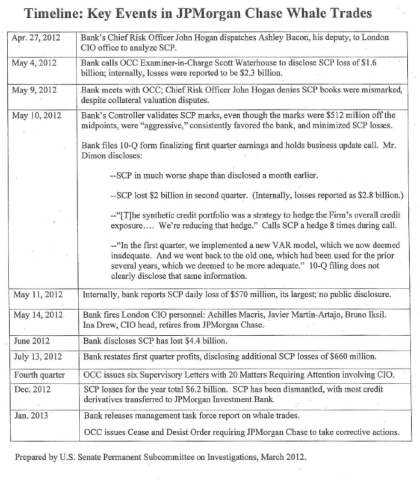

Timeline des Senats

Empfehlungen des Senats

-

When it comes to high-risk derivatives, federal regulators need to know what major banks are up to. We should require those banks to identify all internal investment portfolios that include derivatives over a specified size, require periodic reporting on derivative performance, and conduct regular reviews to detect undisclosed derivatives trading.

-

When banks claim they are trading derivatives to hedge risks, we should require them to identify the assets being hedged, how the derivatives trade reduces the risk associated with those assets, and how the bank tested the effectiveness of its hedging strategy in reducing risk.

-

We need to strengthen how derivatives are valued to stop inflated values. Regulators should encourage banks to use independent pricing services to stop the games; require disclosure of valuation disputes with counterparties; and require disclosure and justification when, as occurred at JPMorgan, derivative values deviate from midpoint prices.

-

When risk alarms go off, banks and their regulators should investigate the breaches and take action to reduce risky activities.

-

Federal regulators should require disclosure of any newly implemented risk model or metric which, when implemented, materially lowers purported risk, and investigate the changes for evidence of model manipulation.

-

Three years ago, Congress enacted the Merkley-Levin provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act, also known as the Volcker Rule, to end high risk proprietary betting using federally insured deposits. Financial regulators ought to finalize the long-delayed implementing regulations.

-

At major banks that trade derivatives, regulators should ensure the banks can withstand any losses by imposing adequate capital charges for derivatives trading. It is way past time to finalize the rules implementing stronger capital standards.

Dokumente zum Senate Hearing

Hearing Video 15.03.2013: Link

Bericht des US-Senats Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations PSI des Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs am 15. März 2013 unter dem Vorsitz von D-Senator Carl Levin.

REPORT - JPMorgan Chase Whale Trades (3-[...]

PDF-Dokument [4.9 MB]

Achtung: Sehr große Datei! (59 MB)

EXHIBITS (JPMC HRG - March 15 2013).pdf

PDF-Dokument [59.3 MB]

OPENING - LEVIN-Carl (March 15 2013)2.pd[...]

PDF-Dokument [72.1 KB]

OPENING - McCAIN-John (March 15, 2013).p[...]

PDF-Dokument [37.3 KB]

STMT - Ashley Bacon (JPMC).pdf

PDF-Dokument [121.7 KB]

STMT - PETER WEILAND.pdf

PDF-Dokument [39.0 KB]

STMT - Michael Cavanagh (JPMC).pdf

PDF-Dokument [626.6 KB]

JP Morgan London Whale

Nachrichten-Chronik

13.08. JPM: Dimon übt sich in Selbstkritik.

"First Reaction was stupid"

"London Whale has been harpooned. Dessicated. Cremated."

"I am going to bury its ashes all over"

"It's a Free. Fucking. Country"

23.08. London Whale: Bruno Iksil nimmt sich Anwalt in Frankreich

23.08. JPM: Ex-CEO Harrison verteidigt Big Banks

06.09. JPM: Vierter Händler, Julien Grout, Franzose, in Verdacht

07.09. JPM: Senat ermittelt neu wegen London Whale

13.09. London Whale: JPM hat Börsenkursverluste wieder aufgeholt

01.10. Irene Tse, CIO-Stellvertreterin für Nordamerika geht Ende 2012

05.10. Barry Zubrow, Regulatory Head, Ex-Chief-Risk-Officer geht

10.10. Douglas Braunstein, CFO, kurz vor Rücktritt

31.10. Martin-Artajo von JPM verklagt

2013

16.01. JPM veröffentlicht internen Untersuchungsbericht

15.03. JPM Hearing: Drew beschuldigt Dimon in vollem Umfang

London Whale. Im Januar 2006 verirrte sich ein Wal in der Themse bis nach London. Trotz enormen technischen Aufwands gelang es nicht, sein Leben zu retten. 6 Jahre später erging es JPMorgan's Chief Investment Office (CIO) ähnlich. Diese interne 400 Mitarbeiter starke Abteilung des Treasury ist fast genauso groß wie die gesamte JPMorgan-Investment Bank und legt das überschüssige bankeigene Vermögen (Proprietary Trading; Eigenhandel) von rund $360 Mio (15% aller JPMorgan-Assets; in 2007 noch $76,5 Mrd) so an, dass es abgesichert ist. Das CIO ist eine sog. Credit Default Swaps Trading Group und verwaltet das Synthetic Credit Portfolio. Der zuständige Händler, der in Frankreich gebürtige Bruno Iksil ("London Whale", "Lord Voldemort") und seine 2 Mitarbeiter hatten die Aufgabe die enormen High Yield Anleihen (Junk Bonds) im Bestand abzusichern. Er hat angeblich jährlich um $100 Mio für die Bank verdient.

Wette. Iksil wettete mindestens $150 Mio auf einen Corporate Bonds Index über 121 große, erfolgreiche US-Unternehmen (Markit CDX North America Investment Grade Index Serie No. 9 - CDX.NA.IG.9) und verkaufte dafür Versicherungszertifikate (Credit Default Swaps) - (Going Long). Jener Index hatte zwar den Status "off-the-run" (am Auslaufen, Laufzeit 2007-2017), war aber immer noch liquide, weil er viele CDOs (Collateral Debt Obligations). Damit wurden die Tranchen des High Yield Index ausgewogen, die JPM gekauft hat - (Going Short). Da zahlte sich aus, als Dynegy und AMR zusammenbrachen. Auf diese Art wäre der Trade sowohl ein Curve Play als auch ein Across Indices. Ein High Yield gegen ein Investment Grade, wobei die High Yield Wette sich vervielfachte, weil es eine Tranche war. Der Long auf IG.9 hätte auch geholfen, den eher teuren Short auf die High Yield Tranchen zu finanzieren. Bruno Iksel handelte auftragsgemäß und nicht betrügerisch. So weit so gut. - Der IG.9 stand im März 2012 bei 105 und stieg Anfang April auf 130. Mitte Mai erreichte er schon 146 und momentan über 160.

Wellen. Schon im November 2010 warnte die British Bankers Association BBA vor der CIO-Gruppe um Achilles Macris, die eine Position von $100 Mrd struktrierten Produkten angesammelt hatte und JPM mit £13 Mrd mehr als 45% der mit britischen Privathypotheken besicherten Derivatemarktes hielt. Leider schlug der wegen seiner schieren Größe des Portfolios "London Whale" genannte Bruno Iksil zu große Wellen am Markt. Er wird als der größte Commission-Zahler oder gilt als derjenige, dem Kreditderivatemarkt gehört. Damit verursachte er den anderen Marktteilnehmern Schäden durch Preisschwankungen. Diese Gegner (Hedge Fonds und Bankenhändler) wetteten nun ihrerseits gegen den Index und kauften CDS. Damit verteuerten diese die Ausfallversicherung mittels Index. Iksil musste nun die einzelnen Komponenten des Index getrennt absichern und war gezwungen, Positionen verlustbringend aufzulösen.

Aufdeckung. Dies blieb in der Fachwelt nicht unbemerkt. Bloomberg (Stephanie Ruhle) und Wall Street Journal (Gregory Zuckerman und Katy Burne) deckten am Freitag, den 6. April 2012 den London Whale auf. Wochenlang versuchte die britische Finanzaufsicht FSA und die amerikanische Derivatenbörsenaufsicht CFTC vergeblich herauszufinden, was das CIO eigentlich macht.

Vertuschung. Am 10.04.2012 meldet WSJ, dass der London Whale Trader keine Trades mehr macht. Jamie Dimon bezeichnet am 13.04.2012 die Aufregung als "tempest in the teapot" (Sturm im Wasserglas). Ende April verzögert JPM die Veröffentlichung des am 27. April fälligen 10-Q Berichtes. Nach Wall Street Journal vom 19.05.2012 wurden Dimon in einer Sitzung am 30. April 2012 von Mitarbeitern Übersichten und Analysen der Verluste übergeben. Dabei verschlug es ihm den Atem. Dimon und der General Counsel, Steve Cutler, der frühere SEC Enforcement Chief, wogen ab, ob sie die Verluste sofort veröffentlichen sollten. Nach Wall Street Journal vom 18.05.2012 ging Dimon mit dem Wissen vom massiven Verlust am 02.05.2012 als Bankenvertreter ind das NY Fed Board Meeting. Er nimmt in seiner Funktion als Aufseher teil, verschweigt dies aber dem Board. - Einen Tag nach der Bekanntgabe des Verlustes, also am 11.05.2012, kam es zu einem Meeting von JPMorgan Vertretern unter der Führung von Don Thompson mit der Derivate-Ausfischtsbehörde CFTC, um "Cross-Border-Issues" zu besprechen. JPM verweigert Einzelheiten (Reuters 22.05.2012).

Bekanntgabe. 5 Wochen später am 10. Mai 2012 um 17 Uhr New Yorker Zeit beruft Jamie Dimon, Chairman und CEO von JPMorgan eine Nottelefonkonferenz mit Analysten und Journalisten ein und erklärte einen Mark-to Market-Verlust im Synthetic Credit Portfolio von mind. $2,3 Mio allein für April und eine weiterer $1 Mrd. in den folgenden Quartalen. Nur 24 Stunden später wird JPMorgan von Fitch um eine Stufe herabgestuft. Zufall? - Dimon nennt die neue Strategie im Sythetic Derivates Portfolio "flawed, complex, poorly reviewed, poorly executed and poorly monitored". Der Trade "may not have violated Volcker Rule, but it violated Dimon principle". "We made a terrible, egregious (ungeheuerlich) mistake". die ank war "sloppy" (schlampig) und "stupid". Der Verlust spiele "into the hands of a bunch of pundits out there". Das offizielle, förmliche Protokoll findet sich am Ende des Artikels.

Aufklärung. JPM schweigt und trägt nichts zur Aufklärung bei. Immer noch nicht bekannt ist das wahre Ausmaß der Wette. Es wird vermutet, dass sie bis zu $200 Mrd beträgt. Die erste ausführliche Stellungnahme liefert JPM in seinem Conference Call am 13.07.2012:

- Interne Ermittlungen haben Beweise zu Tage gebracht, die dem Management Zweifel an der Integrität der Werte oder Marken aufkommen lassen, die die Händler den Trades zuwiesen.

- Die Händler versuchten, den Verlust geringer aussehen zu lassen. Dies ergab sich aus der Auswertung von einer Million Emails und zehntausenden Sprachnachrichten.

- Über die Art der Trades hüllt sich JPM weiterhin in Schweigen.

Hochmut und Fall. JPMorgan waren sozusagen die Götter der Wall Street und die Master of Risk Management. Und eben jener Jamie Dimon ist Director im Board der Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Am 02.02.2012 wurden die CIO-Leiterin Ina Drew sowie die Executives Goldman, Zubrow und Wilmot (Siehe "Personelle Konsequenzen) bei der Federal Reserve vorstellig und versuchten massiv die Dodd-Frank-Regeln soweit aufzuweichen, dass dem Proprietary Trading praktisch keine Grenzen mehr gesetzt sind. Barry Zubrow, Chef der Regulatorischen Angelegenheiten, schrieb am 13.02.2012 in einem Kommentar, "We believe that the final rule should provide for an explicit exclusion for ALM activities". Nun haben sie bewiesen, dass strenge Regulierung die Wettverluste durch sog. long-term-hedge verhindert hätten, obwohl Dimon behauptet, nicht gegen Dodd-Frank-Act verstoßen zu haben - wohl eine reine Schutzbehauptung. - Noch im April, kurz nach der Aufdeckung des London Whale, griff Dimon bei einer von JPM gesponsorten Party Paul Volcker und den Fed-Dallas-Chef Richard Fisher, die beide eine Verkleinerung der Bankenriesen und die Beschränkung ihres Risk Trading befürworteten mit den Worten "infantile" und "nonfactual" an. - Die Bilanz der JPM wurde als "Fortress Balance Sheet" von Dimon hochgelobt. Nun wundert sich die ganze Wall Street, wie innerhalb von 5 Wochen $2 Mrd Verlust entstehen können.

Schmutzige Hände. Am 30. Mai 2012 schockiert Bloomberg (Matthew Leisung, Mary Childs und Shannon Harrington) mit der Meldung "JPMorgan CIO Swaps Pricing Said to differ from Bank". Die bei dem CIO und bei den Credit-Swap-Händlern bein der JPM Investmentbank verwendeten Preise wichen möglicherweise um hunderte Millionen $ voneinander ab und verhinderten so die Entdeckung der Verluste vor dem 10. Mai 2012. Normalerweise gibt es eine zentrale Buchführungsstelle, die solche Preise vergleicht, damit sicher ist, dass keine offene Differenzen existieren. Laut zerohedge.com ist es im CDS-Handel üblich, dass der EOD-Preis im Angebot (Offer) immer markiert wird und entsprechend bei Long Risk Positionen beim Zuschlag (Bid) verwendet wird, so dass - absolut branchengängig - unrealisierte Gewinne schon in der GuV-Rechnung erscheinen und Auswirkung auf Bonuszahlungen haben. Es wird aber vermutet, dass Bruno Iksil und andere Händler die Offers und Bids erfunden oder erzwungen haben (Overriding real Marks). Dies wirft die Frage auf, warum das bankeneigene Preissystem MarkIt (Goldman Sachs, JPM etc.) nicht bemerkt haben. In einem ähnlichen Fall führte das "Mis-Marking" eines Londoner UBS-Mitarbeiters im Oktober 2011 (Ramon Braga) zu Aufsichtsverfahren. Der London Whale könnte sich zu einem der größten Finanzskandale mit den schwerwiegendsten Folgen entwickeln. Diese Meldung fand allerdings bisher kein Echo oder explizite Bestätigung.

Nicht-Überraschungen. Am 11.06.2012 berichten Dan Fitzpatrick, Gregory Zuckerman und Johann Lublin vom Wallstreet Journal, dass einige Top-Executives bereits 2010 über die riskanten Praktiken alarmiert waren. Damals führten Währungsoptionen zu einem Verlust und zu Maßnahmen bei den verantwortlichen Händlern. in 2011 legten Top-Executives des CIO einen Plan zur Abwicklung einer Reihe von großen Trades, der allerdings nicht korrekt umgesetzt wurde. JPM hatte also 2010 noch die Chance, die heutigen Verluste zu verhindern. Doch die Gruppe um Macris, Martin-Aftajo und Iksil waren immer wieder erfolgreich und machten in 2008 $1 Mrd Gewinn mit einer auf fallende Märkten spekulierenden Wette auf selten gehandelte Index-Derivate mit Subprime-Hypotheken "ABX", die zur Absicherung des Immoblienmarktes gedacht waren. Dimon soll teilweise darüber informiert gewesen sein. Währenddessen machte in 2008 aber eine andere Gruppe in New York rund $1 Mrd Verlust auf Fannie Mae und Freddy Mac. Auch in 2010 soll es im London-Office zu einem $300 Mio Währungsoptionsverlust gekommen sein, über den Top-Executives unterrichtet wurden. Daraufhin sei der CFO des CIO Joseph Bonocore, jetzt bei Citigroup, in Sorge an Zubrow, damals Chief Risk Officer von JPM, sowie Michael Cavanagh, damals CFO von JPM, herangetreten sein. Bonocore soll damals bevollmächtigt worden sein, die Positionen zurückzufahren, was von Macris auch getan wurde. Auch darüber soll Dimon unterrichtet gewesen sein. In 2011 seien wieder die hohen Risikopositionen des London-Office aufgefallen. Gegen Ende des Jahres 2011 sollen Drew, Macris und Weiland über die Größe der Credit-Positionen beraten und deren Verminderung beschlossen haben. Das London-Office soll aber weiterhin neue Positionen aufgebaut haben, ohne dass dies genehmigt gewesen sei. Bereits im Sommer 2011 soll Weiland die Risiken begonnen haben zu untersuchen, wurde allerdings im Januar 2012 durch Goldman abgelöst.

Gewinner. Die Gegenspieler des London Whale, das sind Hedge Fonds (z.B. BlueCrest und BlueMountain) sowie Händler bei den Banken gewannen je bis zu $30 Mio. Gerüchte an der Wall Street behaupten laut New York Post, dass der ehemalige Deutsche Bank Propriatery Trader Boaz Weinstein, Chef der Saba Capital Management, die entscheidende Gegenposition aufgebaut und den Wal harpuniert hat. Weinstein soll im Februar 2012 auf einer Charity Harbor Investment Conference den IG.9 empfohlen haben. Doch nicht nur haben die Regulierer über die hochmütigen Wall Street Banker gewonnen und die Federal Reserve Bank of New York als Aufseher über JPMorgan sich mit der angeblich guten Kapitalausstattung der Banken und den Stresstests sowie dem von der Fed neu gegründeten Office of Financial Stabillity Policy and Research blamiert. Auch in Europa gewinnt die Eurozone über die blockierenden EU-Länder. Insbesondere Großbritannien steht nun mit seiner ablehnenden Position unter Druck. Dies gilt nicht nur für die Bankenaufsicht FSA, sondern vor allem den britischen Premier Cameron, der gerade vor ein paar Tagen als Lobbyist seiner Financial City die Umsetzung von Basel III und zuvor den Fiskalpakt sowie die Aufstockung der IWF-Mittel blockierte.

Fehler. Welche einzelnen Positionen Gegenstand des Trades waren, ist bislang noch unbekannt. Jedoch lassen sich zunächst folgende Ursachen beschreiben:

- Synthetic Credit Portfolio: Das Portfolio war nach eigenen Angaben von Jamie Dimon "riskier, more volatile and less effective as a hedge than we had previously thought".

- Funktionsänderung: Das Chief Investment Office ist unter Dimon und Drew von einer strukturellen Risikoausgleichsfunktion zu einem umfassenden Eigenhandel (Proprietary oder Prop Trading) und Investment-Betrieb geworden. Nouriel Roubini stellt am 17.05.2012 fest: "JPMorgan and Dimon were not hedging. They were involved in pure & sheer speculation in arrogant violation of the spirit of the Volcker Rule."

- Interessenkonflikte: Jamie Dimon ist sowohl CEO als auch Chariman (Chef des Verwaltungsrats) und damit sowohl sein eigener Aufseher innerhalb von JPM als auch außerhalb als Bankenvertreter im Board of Directors der New York Fed.

- Eurokrise: Vermutlich hat die Entschärfung der Eurokrise dazu geführt, dass die Absicherungen nutzlos waren und mit Verlust verkauft werden mussten (Vielleicht wurde auch gegen Griechenland und den Euro gewettet?).

- Risikomanagementfehler: Das neue VaR Modell (Value at Risk) ist zu optimistisch. Es ist das Gleiche wie bei Enron. Die Wirtschaftsprüfer PWC PriceWaterhouseCooper haben den VaR Value at Risk geprüft. Dieser hat jedoch die Verluste nicht angezeigt. Der Quartalsbericht Q1 2012 weist noch einen VaR von 67 für das CIO aus. Da der neue VaR sich nicht bewährte, wurde der alte VaR wieder eingeführt. Tatsächlich betrug der VaR plötzlich 129. Offenbar hat also das CIO einen anderen VaR verwendet als der Rest von JPM. Es gibt auch Berichte, dass andere Abteilungen von JPM gegensätzliche Trades zum CIO machten. Zumindest hätte der Wechsel des über lange Jahre bewährten VaR als Rote Flaggen von den Wirtschaftsprüfern erkannt werden müssen, d.h. Anlass zur tieferen Prüfung der ordentlichen Ausführung, Überwachung und Bestätigung des VaR geben müssen. - JPM weist derivative Finanzinstrumente von $71 Billionen aus. Dem steht nur ein Kernkapital von $123 Mrd gegenüber. Insgesamt hält JPM $100 Mrd Risk Bonds. - Die Rote Flagge hätte nach einem Bericht der IFR International Financing Review vom 26.05.2012 schon mit Ablauf des 1. Quartals 2012 hochgehen müssen, als die Long-Position in Investment-Grade Credit sich innerhalb jenes Quartals um $84 Mrd verachtfachte. Dagegen hatte Goldman Sachs z.B. $80 Mrd Short in IG Credit.

- Bilanzierungsfehler. Die verkauften und gekauften Derivate können nicht unter Hedge nach US-GAAP bilanziert werden.

- Organisationsversagen: In der Zeit, in der die Trades platziert wurden, war das Treasury 5 Monate lang nicht besetzt. Der währenddessen für das CIO zuständige Risk Executive war zu unerfahren und ist der Schwiegersohn eines anderen Top-Executives. Der frühere Treasurer Joseph Bonocore verließ im Oktober 2011 abrupt seinen Posten, angeblich aus privaten Gründen. Sein Weggang wurde verheimlicht und erst im März 2012 bekanntgegeben. Bonocore war zuvor 11 Jahre Chief Financial Officer des CIO und kannte die Geschäfte ausgezeichnet. Er nahm als Treasurer jede Woche die Trades des CIO genau unter die Lupe. Ihm wären vermutlich die Probleme aufgefallen. Am 19.05.2012 meldet die New York Times unter Berufung auf Insider, dass Ina Drew schon 2010 das CIO aus den Händen geglitten sei, als sie über längere Zeit krankheitsbedingt immer wieder abwesend war. Die täglichen Conference Calls entwickelten sich während ihrer Abwesenheit zu lautstarken Auseinandersetzungen zwischen ihren Stellvertretern in London, Achilles Macris, und New York, Althea Duersten. Letzere war aufgrund ihrer langjährigen Erfahrung in der Lage, den agressiven Trader Macris in Schach zu halten. Anfang 2011 verschlechterte sich jedoch die Situation als die noch unerfahrene Nachfolgerin von Duersten, Irene Tse, den New Yorker Desk übernahm. Zwar kehrte Drew in 2011 zurück, jedoch überwachte sie nicht mehr täglich die Trades ihrer Desks in London und New York und gewann offenbar nicht mehr die Kontrolle zurück.

Wirtschaftliche Konsequenzen. Für JPM beträgt der Einkommensverlust bis zu $3 Mrd und der Marktwertverlust zunächst $13 Mrd. Der Verlust steigt innerhalb einer Woche bis zum 16.05.2012 um $1 Mrd laut Gerüchten. Die Branche berichtet am 17.05.2012, dass JPM bis zu $5,9 Mrd Verlust haben könnte, bereits $38 Mrd Caps verloren habe und Risk Bonds von bis zu $100 Mrd hält. Der Marktwert von JPM ist seit Bekanntgabe des Verlustes bis zum 17.05.2012 bereits um $25 Mrd auf $33 pro Aktie gefallen. Das CIO hat in den letzten 3 Jahren $5 Mrd Gewinn gemacht, aber nun bereits 2/3 dieses Gewinns wieder verspielt. Bereits am 21.05.2012 schätzen laut CCNMoney Fachleute den möglichen Gesamtverlust auf zwischen $6 bis $7 Mrd. Bis zu diesem Tag hat JPM laut dem Depositor Trust & Clearing Corporation DTCC keine der Positionen abgestoßen. Sobald den Hedge Funds auffällt, dass JPM verkauft, werden sie den Index und Absicherungen kaufen, so dass sich die Verluste für JPM weiter in die Höhe schrauben würden. Doch der Druck zum Verkaufen wirkt von allen Seiten auf JPM: Aufsichtsbehörden, FBI, Senate Banking Committee und die Aktionäre. Am 21.05.2012 sagt Dimon bei einer Investmentkonferenz, dass das JPM Aktienrückkaufprogramm eingestellt wurde, um die Anforderungen an das Eigenkapital besser einhalten zu können. Am 29.05.2012 verkauft JPM $25 Mrd profitable Unternehmensanleihen und andere Wertpapiere mit einem Gewinn von $1 Mrd, um den Verlust auszugleichen. Am 13.07.2012 beziffert JPM den aufgelaufenen Verlust im ersten und zweiten Quartal 2012 auf $5,8 Mrd. Der Gesamtverlust könnte sich bei weiteren Verschlechterung der Märkte auf über $7 Mrd belaufen. Trotzdem kann JPM nun für das erste $4,9 Mrd (um $459 Mio nach unten korrigiert) und für das zweite Quartal $5 Mrd Gewinn vermelden. Dennoch ist der Börsenkurs vom 10. Mai 2012 von $40,74 um 11% auf $36,07 am 13.07.2012 gefallen.

Personelle Konsequenzen. Zunächst wird am 13. Mai 2012 bekannt, dass 3 der zuständigen Excecutives gehen müssen. Am 13.07.2012 bestätigt JPM, dass jene die Firma verlassen haben und vier weitere folgen werden, ohne Namen zu nennen.

- Ina Drew ist seit 2005 als Chief Investment Officer die Leiterin des Risk Managements und bezog mit $15 Mio nach CEO Dimon das zweithöchste Jahresgehalt bei JPM. Sie zählt als Mitglied des Operating Committees zu den engsten Beratern und Vertrauten von CEO Dimon, an den sie direkt berichtet hat. Das Magazin Fortune führt sie auf Rang 8 der 25 höchstbezahlten Frauen. Sie ist die höchstrangigste Frau an der Wall Street und innerhalb von JPM neben der Leiterin des Asset Managements eine der beiden letzten weiblichen Executives. Dennoch war Drew bis zur Bekanntgabe des Verlustes weitgehend unbekannt. Drew hat schon im April ihren Rücktritt angeboten. Sie geht schon 4 Tage nach der Bekanntgabe am Montag, den 14. Mai 2012, mit 55 Jahren in Ruhestand. Ihr Nachfolger wird Matt Zames von JPM's Fixed Income Gruppe und von JPM's Long Term Capital Management LTCM, der positiv bei der Not-Übernahme von Bear Stearns in Erscheinung trat, dessen Abteilung LTCM vor seiner Zeit im Jahr 1998 einen Verlust von $3,6 Mrd verursachte. Am 13.07.2012 berichtet Dimon im Conference Call, dass Drew freiwillig auf erhaltene Vergütungen in Höhe des maximalen in ihrem Vertrag geregelten Clawback verzichtete. Drew erhielt in 2010 und 2011 insgesamt $30 Mio. Wieviel sie davon zurückgibt, wurde nicht bekanntgegeben.

- Barry Zubrow war seit Januar 2012 Head of Corporate Regulatory Affairs und davor Chief Risk Officer der JPM-Bank. Er befürwortete eine Ausnahme in der Volcker-Rule zugunsten mehr Freiheiten im Eigenhandel. Zubrow trat im Januar 2012 von seinem Posten als CRO zurück. Am 05.10.2012 wird bekannt, dass Zubrow auch seine Stelle als Regulatory Head zum Jahresende 2012 aufgeben muss.

- Achilles Macris ist der Chef des Londoner Desks, der die Trades veranlasste. Er arbeitete vor JPM als Proprietary Trader bei Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein und davor bei Cardinal Asset Management. Er wurde 4 Tage nach der Verlustbekanntgabe entlassen. Bis zu seinem Wechsel von Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein zu JPM in 2006 hatte er das Proprietary Trading mit genau den gleichen Produkten (u.a. CDO, ABS, CLO) ähnlich wie jetzt bei CIO aufgebaut. Komplexstrukturierte Produkte bescherten dem damaligen Eigentümer Allianz in Q2 2005 €200 Mio Verlust. Die Allianz versuchte schon 2006 das Risikogeschäft herunterzufahren, konnte aber später in der Finanzkrise einen hohen Verlust von €5,7 Mrd in 2008 nicht mehr verhindern.

- Javier Martin-Artajo ist ein Managing Director am Londoner Desk. Auch er wurde 4 Tage später entlassen. Martin-Artajo war früher bei Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein Chef des Handelsgeschäftes für Derivate und kam mit Macris zu JPM.

- Evan Kalimtgis war bei Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein Leiter der Portfoliostrategie im Kreditgeschäft und folgte Macris und Martin-Artajo nach JPM.

- Bruno Iksils Schicksal scheint noch nicht entschieden. Jedoch wurde ihm sofort die Ausübung der Geschäfte entzogen. Iksil wechselte 2005 von der französichen Investmentbank Natixis zu JPM. Mittlerweile scheint Bruno Iksil in direktem Auftrag von Dimon die Trades unter Kontrolle zu halten und die Abwicklung vorzubereiten. Am 13.07.2012 wird bekannt, dass sich unter den drei entlassenen Managern befindet.

- Irvin Goldman kam im Januar 2008 zu JPM und im Oktober 2010 ins CIO, wo er die Strategie entwickelte und umsetzte. Er wurde im Februar 2012 zum Chief Risk Officer des CIO ernannt und berichtete an Chief Risk Officer John Hogan. Goldman wird ebenfalls seines Postens enthoben. Der Schwager von Goldman, Barry Zubrow, war seit Januar 2012 Head of Corporate Regulatory Affairs und davor Chief Risk Officer der JPM-Bank. Goldman's Schwager, Zubrow, berichtete allerdings nie an ihn. WSJ berichtet am 20.05.2012, dass Goldman bereits in 2008 durch eine einzige Wette JPM einen Verlust zwischen $10 und 15 Mio verursachte. Demnach fiel Goldman im September 2008 bei JPM in Ungnade und wurde entlassen als bekannt wurde, dass Regulierer von NYSE Arca die Handelspraktiken bei Cantor Fitzgerald untersuchten, wo er bis 2007 Händler war und Tradingverluste von $30 Mio verursachte. Cantor Fitzgerald zahlten im April 2010 $250.000 für die Beanstandungen. Bereits im September 2010 stellte Ina Drew aber Goldman wieder ein, um bei der Strategie zu helfen. Es gelang ihm sogar in das Riskmanagement-Committee aufzusteigen, wurde jedoch später wieder von dort entfernt. Insider fragen sich, wie Goldman überaupt ins Riskmanagement kommen konnte ohne mit dem ausgeschiedenen CRO verschwägert gewesen zu sein.

- John Hogan war der Chief Risk Officer der

JPM-Gruppe. Er ernannte Goldman zum Chief Risk Officer des CIO.

- John Wilmot war Chief Financial Officer und wurde ebenfalls freigestellt. Er und Goldman arbeiten weiterhin als Berater für den neuen CIO-Chef Zames.

- Irene Tse übernahm Anfang 2011 von Althea Duersten den stellvertretenden CIO-Posten für den New Yorker Desk. Den ständigen Auseinandersetzungen mit ihrem Pendant in London, Achilles Macris, war sie jedoch nicht gewachsen, wodurch die Übersicht verlorenging. Am 01.10.2012 wird ihr Weggang ab 2013 bekannt. Sie gründet ihren eigenen Hedge Fonds.

- Peter Weiland wird im Oktober 2008 von Drew als Head of Market Risk im CIO eingestellt. Er berichtete direkt an Drew und zunächst indirekt an CRO Zubrow, ab Mitte 2009 direkt an Zubrow und indirekt an Drew. Nachdem im Januar 2012 Goldman CRO im CIO wurde, berichtete Weiland direkt an Goldman. Im Oktober 2012 hört Weiland auf.

- Jamie Dimon, der sich wie ein Gott an der Wall Street benahm, soll nach Meinung der demokratischen Senatorin Elisabeth

Warren (Verbraucherschutzverfechterin und Initiatorin der CFPB-Verbraucherschutzbehörde) zurücktreten. Dimon ist bei JPM seit 01.01.2006 CEO und seit 01.01.2007 Chairman of the Board und war davor

CEO der mit JPM fusionierten Bank One. Das Shareholder Meeting am 15. Mai 2012 trifft keine Beschlüsse. Der Chief Audit Officer von New York fordert JPM am 15.05.2012

auf, Gehälter und Boni zurückzufordern. Finanzminister Geithner (Präsident der New York Fed 2003-2008) sieht am 17.05.2012 Dimon als Imageproblem für die New York Fed. Dimon ist dort im Board of

Directors einer der 3 Bankenvertreter (Class A Member). Seine Amtszeit im Fed-Board begann 2007 und endet planmäßig am 31.12.2012. Seine letzten Tage scheinen jedoch gezählt, als am 18.05.2012 das

Wall Street Journal meldet, dass er den massiven Verlust im von ihm besuchten Fed Board Meeting verschwieg, obwohl er davon wusste. Am 15.03.2013 wird in der Senatsanhörung bekannt und von Drew

bestätigt, dass Dimon seit Januar 2012 informiert war und in einer Email vom 23.01.2012 die Erhöhung der Risikolimits mit "I approve" höchstpersönlich genehmigte. Damit dürfte seine Karrierre bei

JPMorgan beendet sein.

- Investment Banking Unit: Als neuer Senior Vice Chariman wird 23.05.2012 Joseph A. Walker vorgestellt. Er war 22 Jahre bei JPMorgan und verließ die Bank 2001 für General Motors.

- Lou Lebedin war seit März 2012 Global Prime Brokerage Chief bzw. seit 2008 Co-Chief bevor er von Bear Stearns kam. Seine Entlassung wurde am 26.05.2012 bekannt.

- Risk Policy Committee. Den Vorsitz hält bislang noch James Crown, Präsident der Investmentfirma Henry Crown & Co. und Ex-Direktor bei General Dynamics. Weiteres Mitglied ist Ellen Futter, langjährige Präsidentin von Amerika's Naturgeschichtemuseums. Sie war früher im Audit Commtttee bei Bristo-Myers, einem New Yorker Pharmaunternehmen, das 1999 wegen eines Bilanzskandal $300 Mio Bußgeld zahlen musste, um Strafverfahren abzuwenden. Futter war bis Juli 2008 in AIG's Compliance und Governance Committee tätig. Ferner gehört auch seit 2008 David Cote, Chief Executive von Honeywell International Inc. zum Risk Committee. Mindestens ein neues Mitglied wird hinzukommen oder jemanden ersetzen. Im Gespräch sind die riskerfahrenenTimoth Flynn, Chairman von KPMG International, und James Bell, ehemaliger CFO des Aerospace-Bereichs von Boeing.

Firmeninterne Konsequenzen. Die Aktionärsversammlung bestätigt am 15.05.2012 die Doppelfunktion von Jamie Dimon als CEO und Chairman. Der neue Chef des CIO ändert den Fokus auf "Hedging Risk". Bei dem Conference Call am 13.07.2012 schildert JPM folgende Maßnahmen:

- Von einigen Managern werden 2 Jahre Vergütungen zurück verlangt (Clawbacks)

- Die für das Versagen verantwortliche Abteilung wurde aufgelöst

Regulatorische Konsequenzen. Entgegen der Behauptung von Jamie Dimon ist nach Ansicht des Professors von Maryland, Michael Greenberger, die Volcker-Rule verletzt. Allerdings sind die betreffenden 2 Aspekte des Dodd-Frank-Acts noch nicht in Kraft getreten. Im Titel VII über die Over-The-Counter (OTC) Derivate wird verlangt, dass ein Clearing an einer Börse und transparente Ausführung erfolgt. Wenn die Trades gegen eine Institution gerichtet sind, muss nach diesen Regeln zusätzliches Kapital bereitgestellt werden. Das Clearing-Haus hätte regelmäßig Preise bestimmt und bei Abweichungstendenzen eine zusätzliche Margin (Sicherheit) verlangt. Doch dieser Titel VII ist weiterhin heftig umkämpft. Klar ist nur, dass der London Whale Trade nicht passiert wäre, wenn der nach dem Großen Crash erlassene Glass-Steagall Act von 1933 (Trennung von Geschäftsbanken von Investmentbanken) noch gegolten hätte. Er wurde mit dem Gramm-Leach-Bliley-Act 1999 unter Präsident Clinton auf Empfehlung von John Dugan (Comptroller of the Currency 2005-2010) aus dem Jahr 1991 zur Deregulierung des Finanzsystems aufgehoben. Am 15.05.2012 nehmen de Regulierer die Beratungen über die Volcker-Rule wieder auf. Natürlich versucht Dimon und JPMorgan menschliches Versagen für den Skandalverlust verantwortlich zu machen, um so wenig wie möglich Grund für schärfere Regulierung zu geben. Jedoch macht sich bereits am 21.05.2012 der Chef der Derivateaufsicht CFTC Gary Gensler dafür stark, auch die Auslands-Töchter der US-Banken einer harten Volcker-Rule zu unterwerfen. Banken, die stark in Derivaten tätig sind, werden zu Swap-Dealern und müssen höhere Kapitalanforderungen und Auflagen erfüllen. Die Ähnlichkeit des Londoner CIO von JPMorgan zur Londoner Derivate-Unit von AIG ist doch zu frappierend. Im Conference Call vom 13.07.2012 deutete JPM an, dass die Aufsicht zum Schluss kommen könnte, dass JPM's Aufsicht und Risikomanagement zu den problematischen Statements geführt haben.

Juristische Konsequenzen.

- FSA (Financial Services Authority). Kurz nach Aufdeckung des London Whale Anfang April 2012 leitete die britische Bankenaufsicht FSA Untersuchungen ein. Zur Klärung wurden Auskünfte von JPM eingeholt.

- CFTC (Commodity Futures Trading Commission). Die amerikanische Derivate-Aufsicht CFTC leitet ebenfalls Anfang April Voruntersuchungen ein, ohne Aufsichtsmaßnahmen zu ergreifen. Jedoch kam es unterdessen zum Verlust, ohne dass die FSA oder CFTC eingreifen könnte. Am 04.06.2012 berichtet Silla Brush in Bloomberg Businessweek, dass die CFTC am 21.06.2012 über Richtlinien für die Ausdehnung der Dodd-Frank Act-Regeln auf Übersee Swap-Handel abstsimmen will.

- SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission). Am 11. Mai 2012 meldet die amerikanische Börsenaufsicht den Beginn von Untersuchungen.

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Die für JPMorgan regional zuständige Bankenaufsicht NY Fed, in deren Board Jamie Dimon einen der 3 gesetzlich vorgeschriebenen Bankenvertretersitze inne hält, startet ebenfalls Ermittlungen.

- OCC (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency). Das OCC gerät unter Druck, weil es die Praktiken von JPMorgan bislang als gesetzeskonform eingestuft hat. Der seit April amtierende neue OCC-Chef Thomas Curry will nun die Banken strenger beaufsichtigen.

- Aktionärsklagen. Als erste Kanzlei reichte Robbins Geller eine 18-seitige Klage ein, die eher als Platzhalter zu dienen scheint. Eine weitere Anwaltskanzlei (Finklestein & Krinsk) reicht am 15.05.2012 in Manhattan für den Großaktionär Saratoga Advantage Trust eine 31-seitige Klage nebst Sammelklageantrag gegen JPM sowie Dimon und Finanzchef Douglas Braunstein wegen des Verlustes und des Kursabsturzes ein. Sollte der Sammelklagenantrag genehmigt werden, so werden Anleger repäsentiert, die zwischen 13. April und 10. Mai Aktien hielten. (Siehe Dokumente unten). Dimon wird vorgeworfen: Delaying the announcement.

- FBI. Das FBI in New York leitet am 15.05.2012 Vorermittlungen im Auftrag des Justizministeriums (DOJ Department of Justice) ein und prüft die Bilanzierungspraktiken und Veröffentlichungen über die Trades.

- Senate Banking Committee. Am 14. Mail 2012 kündigt das Senate Banking Committee eine eigene Untersuchung an. Der Kongress hat Dimon zu einer öffentlichen Befragung ("Grilling") eingladen und dieser hat am 17.05.2012 zugesagt. Die Befragung soll nun am 07.06.2012 stattfinden. Kritiker unterstellen aber, dass der Committee Chair Tim Johnson von South Dakota nicht beißen wird, weil einer seiner gößten Wahlkampfspender seit Jahren JPMorgan Chase heißt. Außerdem ist Dwight Fettig Staff Director des Senate Banking Committed, der früher als Lobbyist für JPMorgan, Freddie Mac und andere Finanzkonzerne tätig war (republicreport.org vom 22.05.2012).

- Zivilklagen. JPM Conference Call 13.07.2012: Falls die Aufsichtsbehörden zur Erkenntnis kämen, dass

JPM-Mitarbeiter mit ihren Täuschungen JPM zur Berichterstattung falscher Finanzzahlen veranlasst haben, könnten Zivilklagen auf diese Mitarbeiter und auch JPM zukommen. DoJ, SEC und andere

Aufsichtsbehörden, darunter eine in UK, untersuchen derzeit den Verlust.

Offene Fragen. Am 19.05.2012 postet Simon Johnson auf baselinescenario.com die Notwendigkeit einer unabhängigen Intersuchung von JPMorgan Chase:

- Was war genau der Trade und wer genehmigte und prüfte ihn?

- In welchem Maße wurden die Fehler durch bestimmte quantitative Modelle ermöglicht oder geduldet, z.B. das allseits bekannte Value at Risk?

- Was wußte Dimon und wann wußte er es? Gab es eine Unterrichtung des Boards und der Aktionäre zu einer passenden Zeit?

- Hat der Board adäquate Tiefe der Erfahrung hinsichtlich der Dimensionen des Riskmanagements?

- Welche Interaktionen hatte Dimon oder irgendein anderer seiner Kollegen mit der Federal Reserve Bank von New York bevor und während die Verluste auftraten? Dimon ist Board Member mit dem Status als Advisor. Aber bei was genau hat er sie in den jüngsten Monaten und Jahren beraten, insbesondere hinischtlich Risk Management und Kapitalanforderungen in systemisch wichtigen Banken?

Andrew Ross Sorkin führt in der New York Times folgende Fragenliste für Dimon im Dealbook auf:

- On April 13, about a month before you disclosed the $2 billion trading loss, you called speculation about outsize risks in your chief investment office “a tempest in a teapot.” What, if any, analysis had you personally conducted before making that statement? Do you believe you had all of the appropriate information at the time? If not, why not? Do you believe that you were provided with misinformation or were otherwise purposely misled?

- The firm’s chief investment office recently changed the way it calculated how much money the unit could lose in a given day. That appears to be one of the reasons so much could be lost so quickly. What were you told about the rationale for making the change? How involved were you in the decision? And were regulators briefed before the change?

- Your chief investment office valued or marked certain securities at higher values than other divisions within the bank valued them, according to people briefed on the group’s valuations. Is that true? If so, how is it possible that one division could value the exact same asset differently from a different division? Are there other divisions of the bank that value assets differently? What steps have you taken to synchronize the monitoring and valuing of securities and other assets across the bank’s divisions?

- In a letter to the Securities and Exchange Commissioncommenting on the Volcker Rule, your firm took great pains to advocate for broad macroeconomic portfolio hedging, the same kind of hedging that took place in your chief investment office. You made the case that your firm successfully put hedges in place ahead of the financial crisis that were instrumental to the firm’s success. However, you now point out that under the Volcker Rule, some of those trades would not have been permitted because “(1) the actions taken were forward looking and anticipatory; (2) the firm’s purchases of the credit derivatives may not have been deemed ‘reasonably correlated’ with the underlying risk, as different instruments were used to effect the hedging strategy than the assets giving rise to the risk; and (3) the gains realized upon the unwind of the hedges could have been determined to be larger than the countervailing risks.” While the firm should be commended for its success in navigating the financial crisis, why should the trades referred to in your letter be considered hedges and not speculative bets?

- If portfolio hedging were banned by the Volcker Rule or other legislation, what would be the impact on JPMorgan’s customers? Would you make fewer loans? Would prices go up?

- Your chief investment office has put money in corporate bonds as opposed to less risky Treasury bonds, then used derivatives to bet on directions of the market. That indicates that the purpose of the unit, unlike at some of your competitors, is to generate profit rather than protect the bank from losses. Should the investment office be a profit center? What was your role in the unit taking on more risk?

- More than 100 regulators work inside your headquarters to monitor and regulate your firm. Why did they miss this? When did they first raise questions about the London trades? Were they provided with all of the information requested? Were they ever misled? Did anyone at the firm ever push back on concerns that the Fed or regulators from any other agency raised? Most important: Do you believe that the regulators should have been able to spot these trades? And if not, what could, or should, be done to help them identify such a risky trade?

- Ina Drew, the chief investment officer in charge of the London group that made the bad trades, retired within days of your disclosure of the losses. Ms. Drew was paid $14.1 million in 2011, one of the highest at your firm and in the industry. You have said you would consider clawbacks for people involved in the losses. Your proxy statement says that an employee’s pay will be clawed back if he or she “engages in conduct that causes material financial or reputational harm.” Have you clawed back any of her previous income or that of others in the group? If yes, how much? If not, why not? Also, did you strike any financial arrangement with Ms. Drew as part of her agreement to retire? Have you struck financial deals with any of the other executives who are expected to leave the firm by the end of the year? If so, please provide the details and the business decision to do so.

- Bruno Iksil, your trader nicknamed the London Whale, had made a $100 billion derivatives bet to create what your chief investment office considered a hedge. However, such a large trade made JPMorgan virtually the entire market for a certain kind of derivative, which makes it particularly difficult to unwind. Given JPMorgan’s size, is it too big to hedge?"

(Prepared) Testimony of Jamie Dimon

Chairman & CEO, JPMorgan Chase & Co.

"Before the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Washington, D.C.

June 13, 2012

Chairman Johnson, Ranking Member Shelby, and Members of the Committee, I am appearing today to discuss recent losses in a portfolio held by JPMorgan Chase’s Chief Investment Office (CIO). These losses have generated considerable attention, and while we are still reviewing the facts, I will explain everything I can to the extent possible.

JPMorgan Chase’s six lines of business provide a broad array of financial products and services to individuals, small and large businesses, governments and non-profits. These include deposit

accounts, loans, credit cards, mortgages, capital markets advice, mutual funds and other investments.

What does the Chief Investment Office do?

Like many banks, we have more deposits than loans – at quarter end, we held approximately $1.1 trillion in deposits and $700 billion in loans. CIO, along with our Treasury unit, invests excess cash

in a portfolio that includes Treasuries, agencies, mortgage-backed securities, high quality securities, corporate debt and other domestic and overseas assets. This portfolio serves as an important

source of liquidity and maintains an average rating of AA+. It also serves as an important vehicle for managing the assets and liabilities of the consolidated company. In short, the bulk of CIO’s

responsibility is to manage an approximately $350 billion portfolio in a conservative manner.

While CIO's primary purpose is to invest excess liabilities and manage long-term interest rate and currency exposure, it also maintains a smaller synthetic credit portfolio whose original intent was

to protect – or “hedge” – the company against a systemic event, like the financial crisis or Eurozone situation. Among the largest risks we have as a bank are the potential credit losses we could

incur from the loans we make. The recent problems in CIO occurred in this separate area of CIO’s responsibility: the synthetic credit portfolio. This portfolio was designed to generate modest returns

in a benign credit environment and more substantial returns in a stressed environment. And as the financial crisis unfolded, the portfolio performed as expected, producing income and gains to offset

some of the credit losses we were experiencing.

What Happened?

In December 2011, as part of a firmwide effort in anticipation of new Basel capital requirements, we instructed CIO to reduce risk-weighted assets and associated risk. To achieve this in the

synthetic credit portfolio, the CIO could have simply reduced its existing positions; instead, starting in mid-January, it embarked on a complex strategy that entailed adding positions that it

believed would offset the existing ones. This strategy, however, ended up creating a portfolio that was larger and ultimately resulted in even more complex and hard-to-manage risks.

This portfolio morphed into something that, rather than protect the Firm, created new and potentially larger risks. As a result, we have let a lot of people down, and we are sorry for it.

What Went Wrong?

We believe now that a series of events led to the difficulties in the synthetic credit portfolio. Among them:

• CIO’s strategy for reducing the synthetic credit portfolio was poorly conceived and vetted. The strategy was not carefully analyzed or subjected to rigorous stress testing within CIO and was not

reviewed outside CIO.

• In hindsight, CIO’s traders did not have the requisite understanding of the risks they took. When the positions began to experience losses in March and early April, they incorrectly concluded that

those losses were the result of anomalous and temporary market movements, and therefore were likely to reverse themselves.

• The risk limits for the synthetic credit portfolio should have been specific to the portfolio and much more granular, i.e., only allowing lower limits on each specific risk being taken.

• Personnel in key control roles in CIO were in transition and risk control functions were generally ineffective in challenging the judgment of CIO’s trading personnel. Risk committee structures and

processes in CIO were not as formal or robust as they should have been.

• CIO, particularly the synthetic credit portfolio, should have gotten more scrutiny from both senior management and the firmwide risk control function.

Steps Taken

In response to this incident, we have taken a number of important actions to guard against any recurrence.

• We have appointed new leadership for CIO, including Matt Zames, a world class risk manager, as the Head of CIO. We have also installed a new CIO Chief Risk Officer, Chief Financial Officer, Global

Controller and head of Europe. This new team has already revamped CIO risk governance, instituted more granular limits across CIO and ensured that appropriate risk parameters are in place.

• Importantly, our team has made real progress in aggressively analyzing, managing and reducing our risk going forward. While this does not reduce the losses already incurred and does not preclude

future losses, it does reduce the probability and magnitude of future losses.

• We also have established a new risk committee structure for CIO and our corporate sector.

• We are also conducting an extensive review of this incident, led by Mike Cavanagh, who served as the company’s Chief Financial Officer during the financial crisis and is currently CEO of our Treasury & Securities Services business. The review, which is being assisted by our Legal Department and outside counsel, also includes the heads of our Risk, Finance, Human Resources and Audit groups. Our Board of Directors is independently overseeing and guiding these efforts, including any additional corrective actions.

• When we make mistakes, we take them seriously and often are our own toughest critic. In the normal course of business, we apply lessons learned to the entire Firm. While we can never say we won’t

make mistakes – in fact, we know we will – we do believe this to be an isolated event.

Perspective

We will not make light of these losses, but they should be put into perspective. We will lose some of our shareholders’ money – and for that, we feel terrible – but no client, customer or taxpayer

money was impacted by this incident.

Our fortress balance sheet remains intact: as of quarter end, we held $190 billion in equity and well over $30 billion in loan loss reserves. We maintain extremely strong capital ratios which remain

far in excess of regulatory capital standards. As of March 31, 2012, our Basel I Tier 1 common ratio was 10.4%; our estimated Basel III Tier 1 common ratio is at 8.2% – both among the highest levels

in the banking sector.1 We expect both of these numbers to be higher by the end of the year.

All of our lines of business remain profitable and continue to serve consumers and businesses. While there are still two weeks left in our second quarter, we expect our quarter to be solidly

profitable.

In short, our strong capital position and diversified business model did what they were supposed to do: cushion us against an unexpected loss in one area of our business.

While this incident is embarrassing, it should not and will not detract our employees from our main mission: to serve clients – consumers and companies – and communities around the globe.

• In just the first quarter of this year, we provided $62 billion of credit to consumers. • Over the same period we provided $116 billion of credit to mid-sized companies that are the engine

of growth for our economy, up 16% year on year.

• For America’s largest companies, we raised or lent $368 billion of capital in the first quarter to help them build and expand around the world.

• We are one of the largest small business lenders and the leading Small Business Administration lender in America, providing $17 billion in credit to small businesses in 2011, up 70% year on year.

In the first quarter, we provided over $4 billion of credit to small businesses, up 35% year on year.